OCD symptoms often develop for minors during the tween or teen years, and most people are diagnosed before age 25.

If you’re looking for help for your minor child with OCD, you’re not alone. It’s common for OCD symptoms to first show up in childhood: two of the most common times to develop OCD are during the tween years or the late teen years. In general, most people with OCD start noticing symptoms before age 25.

Research suggests boys tend to devleop OCD at an earlier age than girls do. However, every kid is different. For example, I’m a children’s OCD therapist who was also diagnosed with OCD as a child, and my symptoms started at age 7.

Regardless of your child’s age, your support as a parent is really important. Kids—especially young ones—need their parents to be involved in the therapy process, and this is especially true when it comes to OCD therapy. The good news is that your support will have a huge, positive impact on your chid’s recovery from OCD. In this post, you’ll learn 5 simple ways you can help your minor child—and yourself—through OCD

Identifying OCD Symptoms in Minors

It’s not always easy to identify OCD symptoms in children. Kids are often aware that the worries OCD gives them are unusual, and will try to mask their symptoms as a result They may feel embarassed, ashamed, or afraid of the thoughts they’re having. They don’t want other people to know about these weird thoughts, so they cover them up instead.

Also, a child’s OCD symptoms might not fit the mold of what we expect OCD to look like. We might envision a very neat, orderly person who’s focused on avoiding germs or keeping things organized. In reality, OCD can look many different ways, and the signs are often very subtle. It’s entirely possible for a child with OCD to be messy, disorganized, or totally unworried about dirt or germs.

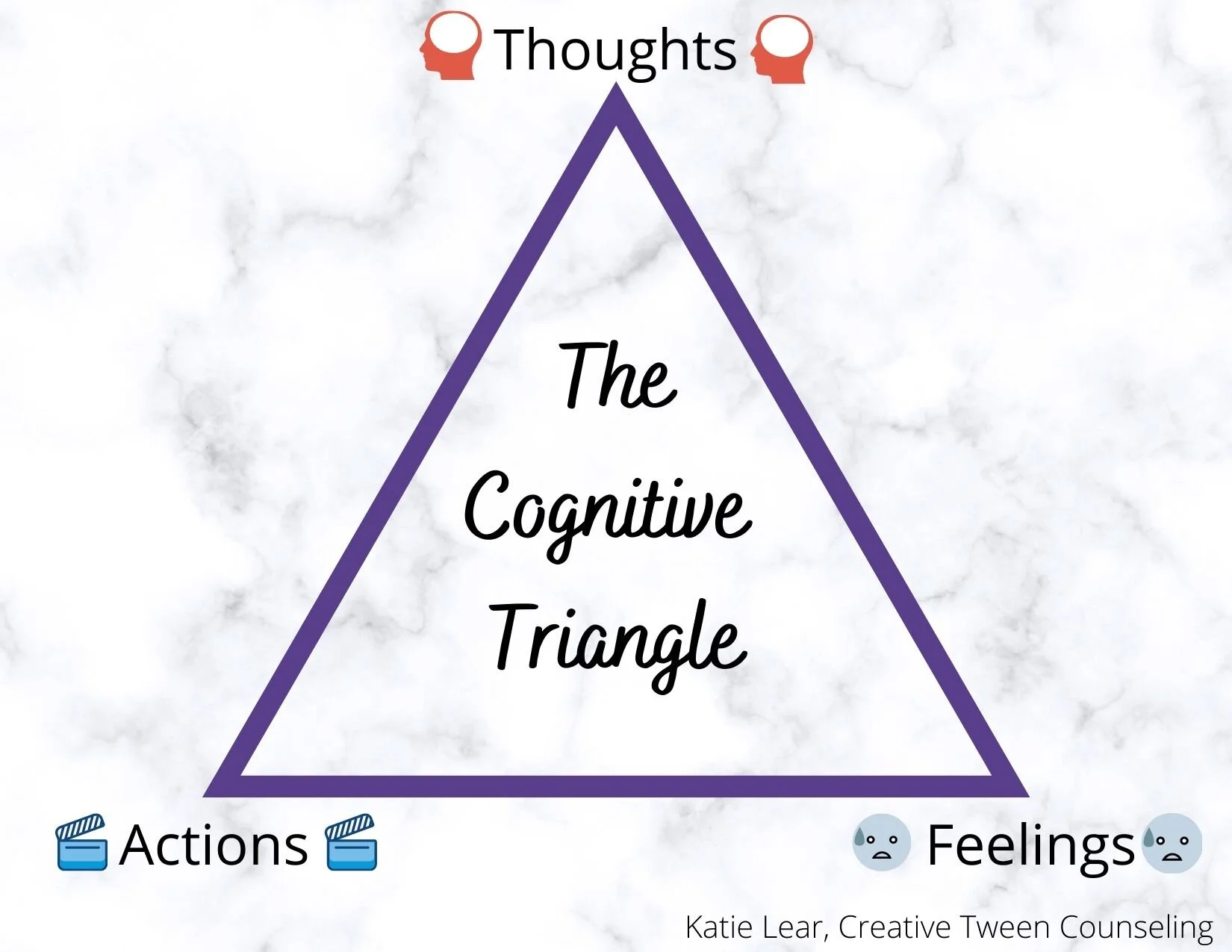

People with OCD have two things in common: obsessive thoughts and compulsive behavior. An obsession is an unwanted thought, worry, or mental image that pops up at unwanted times. It’s hard to get rid of, and causes a lot of anxiety or distress. In order to deal with these obsessions, OCD sufferers feel like they have to do something to alleviate their anxiety. This repeated behavior is called a compulsion.

Common obsessions for kids with OCD include:

Worries related to getting sick, throwing up, or contracting germs

Fear about somehow losing control and doing something bad, like hurting themselves or someone else (even though they don’t want to)

Thoughts that if they don’t do something just right, something terrible could happen

Worries about bad things happening to loved ones

Doubts about whether or not they may have misbehaved or done something wrongj

Worries about sexuality or being gay in children who aren’t otherwise questioning their identity

You may notice compulsive behaviors like these in your minor child with OCD:

Checking and-rechecking that they’ve done something, like turned off a light switch

Creating rituals that have to be done exactly the right way, such as a specific process for washing hands or a rigid bedtime routine

Excessive cleaning, showering, or handwashing

Repeatedly asking for reassurance about things, even after they’ve been given an answer

Confessing bad thoughts or possible misbehavior to a parent

Repeatedly touching or counting objects, or repeating actions to make them symmetrical (like tapping one leg and then the other)

The tricky thing about OCD is that compulsions never permanently get rid of an obsessive worry. This means that people get stuck in a cycle of doing their compulsive behavior over and over in order to feel some sense of relief.

Five Ways to Help Your Minor Child with OCD

As a parent, you can help your child understand their symptoms and work together as a team to combat OCD.

Now that we’ve reviewed the symptoms of OCD, let’s talk about how you can help your child to cope. OCD is a stressful diagnosis not just for the child who is suffering, but their entire family. Keep reading to learn ways to demystify OCD, reduce feelings of shame and loneliness, and start looking at OCD from a different perspective. These 5 steps will help you and your child look at OCD in a new light, so you can start working on healing together.

These techniques aren’t a replacement for therapy (more on that below), but they are tried-and-true approaches that I teach in my child therapy office. They’re also exactly the kinds of things that I think would have helped my family when I was a kid. If you’ve just noticed OCD symptoms in your minor child and you’re not sure what to do, start here.

#1: Help Your Child Understand OCD

I mentioned above that kids with OCD often know that their thoughts are unusual. That’s because OCD is ego dystonic: this means that the thoughts it causes go against a person’s temperament and values. They can feel weird, confusing, or “other,” almost like they’re not coming from you. Often, OCD preys on a child’s worst fears: peaceful kids may experience violent images, responsible children might worry about mistakes, and typically subdued kids can suddenly have thoughts about losing control and doing something inappropriate.

As you can imagine, this is really upsetting. Kids with OCD may worry they’re going crazy or that something is deeply wrong with them. They may also assume they’re the only one having these “weird” thoughts. This is especially true if their obsessions are about something embarrassing, shameful, or taboo.

You can help your child understand OCD so they feel less alone. Learning how OCD works can help kids realize that their symptoms aren’t so unusual after all, and that there is treatment that will help. Start by teaching a few important facts about OCD:

Nothing a person does causes OCD. It’s mostly genetic, and not anybody’s fault.

Just because you have a bad thought doesn’t mean you’ll act on it. In fact, people with OCD tend to have obsessive thoughts about things they’d never do in real life.

OCD isn’t dangerous: it’s just a little glitch or “hiccup” that happens in the brain.

You can fight back against OCD by not doing what it tells you to do: this is hard, but it teaches your OCD who is boss!

Reading books together is a great way to get these points across. It gives parents language they can use to explain OCD, and seeing that someone has gone through the trouble of writing a book can reassure kids that they really aren’t alone. What to Do When Your Brain Gets Stuck is a classic, and many people enjoy Up and Down the Worry Hill, too.

Your child might also appreciate taking a look at a list of celebrities who have OCD. About 1.2% of people are diagnosed with OCD. This means there are plenty of public figures who have been affected by it, including David Beckham, Daniel Radcliffe, and Camila Cabello.

#2: Be a United Team with Your Child Against OCD

Your child can separate herself from her symptoms by drawing a picture of what she imagines OCD looks like.

Battling OCD is not easy work. You have to do exactly the thing your brain is saying not to do in order to feel better! This can put parents at odds with their kids, because parents are the ones who have to hold bnoundaries and stick with the plan to overcome OCD. It’s important to remind your child (and yourself) that this fight is not you against them: it’s the two of you against OCD.

You can maintain a united front by imagining OCD as a little character or creature that is totally separate from your child. This is called “externalizing:" it’s a tool we use in therapy to help separate a problem from the person suffering from it. Externalizing OCD can help you feel like you’ve got a common enemy. It also reduces some of the shame and frustration kids feel when they experience thoughts and urges beyond their control.

Encourage your child to give their OCD a name: kids often choose something funny and nonthreatening, like “Bob” or “Dr. Annoying.” Your child might also enjoy drawing a picture of what they imagine their OCD would look like. Creating this kind of OCD character is a coping skill I use with almost all kids at the beginning of treatment (you can check out other OCD coping skills here).

Next time you notice your child saying or doing something related to their OCD, don’t blame them—blame Bob.

#3: Don’t Fall Into the Reassurance Trap

It’s only natural to want to comfort your child when they’re worried. As parents, we probably offer reassurance all day without thinking twice. Sometimes, a simple “it’s okay” or “everything will be alright” is all a child needs to hear in order to feel better.

Unfortunately, the usual rules don’t apply to OCD. Reassurance typically does more harm than good: even though it helps kids feel better in the short term, it fuels their anxiety in the long run. Reassurance-seeking is the most common OCD compulsion I see among kids in my therapy practice. Cutting back on reassurances can go a long way toward helping your child.

You might notice your child asking you the same question over and over, even after you’ve already explained that things will be fine. That’s because reassurance only quiets the OCD worries for a little bit. The OCD worries always come back, which means your child has to ask again to get relief. Over time, this pattern actually makes the symptoms worse.

One of the big goals of OCD treatment is to help parents gradually stop enabling their child’s OCD by giving into its demands. This means gradually scaling back on giving reassurance if you’ve been doing it a lot. If your child’s symptosm are mild, you may have good luck doing this on your own at home. If you’ve been stuck in this pattern for a while, a therapist can help you to gently break the cycle.

#4: Research Therapists who Treat Minors with OCD

Databases like the one provided by IOCDF can help you find therapists who specialize in treating OCD in minors.

While some minor children will recover from OCD without therapy, many will need extra help. Research has found that for about 1 in 5 kids, symptoms will resolve on their own, without treatment. For that remaining 4 out of 5, therapy will help kids get back on track and manage their symtpoms.

It might sound daunting at first to hear that most kids with OCD require therapy to recover. However, there are a couple of big silver linings here. The first bit of good news is that we have a form of therapy called ERP that’s been designed specifically for treating OCD, and it is highly effective. We also know that entering therapy early in life helps people with childhood-onset OCD make a much fuller recovery. That’s good news for your child!

Working with OCD is a specialty: not all therapists have extensive training in this area. The same is true for working with children. Finding a therapist who specializes in both OCD and working with minors might require a little extra legwork. The International OCD Foundation (IOCDF) has a searchable list of therapists who are trained in ERP, the “gold standard” treatment for OCD, including therapists who have been specifically trained to treat children. You can also run a search on Psychology Today to look for therapists in your area who offer ERP and see kids or teens.

Not all therapy therapy training programs don’t cover OCD or child therapy in tons of detail, so it can help to ask prospective therapists what their training and experience is with these two groups. Registered Play Therapists often have lots of training working with kids. ERP is the most common, best-researched therapy for OCD treatment. You can also ask more general questions, like the ones in this post, to get a sense for whether a therapist seems like the right fit for your family.

#5: Practice Self-Care So You Can Support Your Child

OCD is tough for kids, but it’s incredibly draining for their families, too. The bigger OCD symptoms grow, the more time and energy it takes to keep up with all the compulsive behaviors and rituals. Families—and parents especially—may feel like they’re bending over backwards or walking on eggshells to avoid triggering their child’s OCD. And even with all that effort, new worries pop up, seemingly out of nowhere.

It’s common for parents to feel exhausted, hopeless, or even resentful when they’ve been dealing with a child’s OCD for a long time. Kids often pick up on this tension, which adds extra stress to an already stressful situation. Gradually facing fears through OCD treatment is the most surefire way out of this vicious cycle, but it requires a lot of work, too. You’ll need a lot of patience and compassion to help your child through therapy.

Treating OCD is more of a marathon than a sprint. Resist the temptation to put yourself last on the to do list, and make sure you’re setting aside time to do whatever will help you continue to show up for your child. Date nights, exercise, time away from parenting, or watching something on TV that isn’t Bluey all count. You can also ask to speak to your child’s counselor in private or seek out your own therapist if you need to vent and get your own support.

OCD Therapy for Minors in North Carolina

You can help your child through OCD with the support of a therapist. I provide OCD treatment for kids and their families throughout North Carolina, New York, and Florida.

I hope you’ve found this article helpful, and that it gives you some options to try while you consider looking for a therapist. If you’re looking for OCD counseling for your child, I may be able to help! I’m physically located in Davidson, North Carolina, and can meet with local children in-person or online. I’m also available for virtual sessions with families in Florida and New York. You can learn more about my practice or email me to get started.

Looking for more information on how OCD affects minors? Check out some of my other posts:

Can a Child Have Mild OCD?

What Are the 4 Types of OCD?

How to Help a Child with Intrusive Thoughts

Does Childhood OCD Go Away?