Children’s grief doesn’t always look the way we expect it to. With kids, sometimes still waters run deep. If your child has just experienced a loss and they aren’t talking about it, are they still feeling it? Should you bring it up to them, or wait until they come to you with questions? How can you tell if your child is processing their grief in the way they need to in order to move forward and heal?

All children are capable of grief: they just show their feelings differently than adults do. In this post, we’ll take a look at the key differences between child and adult grief. We’ll also go over how children of different age groups tend to grieve, so you can keep an eye out for common signs of grief in your own child.

Children’s Grief Can Be Hard to Recognize

Back in the days of Freud, experts believed young children weren’t capable of feeling grief, because they couldn’t fully understand what death meant. Today, we know that isn’t true at all: even little babies can sense when a caregiver has left. Children don’t need a complete understanding of death to mourn the loss of a loved one.

When most of us think of grief, we imagine lots of crying, maybe even depression. We might imagine grieving people talking a lot about how much they love and miss the person who died. We might assume it will be a long time before the griever starts to feel or act like themselves again.

Kids’ grief doesn’t always fit this traditional mold. While many children will cry or feel sad after a loved one dies, others may not. Their feelings and reactions to grief might change rapidly or seem short-lived. Because their grief looks so different, it’s easy to miss. Parents may notice behavior changes or physical symptoms in their children, but not recognize them as being related to grief.

Difference 1: Delayed Reactions

When a loved one dies, children have to deal with a huge shock that they don’t fully understand. In addition to dealing with the loss, kids often have to figure out what exactly death is, and what it means for them. Most children also don’t have a lot of prior experience with grief, so they may not know how they are “supposed” to react when faced with such horrible news.

Kids can grieve even if they aren’t old enough to fully conceptualize death. However, it might take them longer to process what has happened and begin showing their feelings about it. Grievers of all ages experience shock and denial after death. For children, this might include wondering if a loved one might still be alive, or wishing they could come back to visit. Little children may ask repeated questions about the death in an attempt to understand it better.

Once time has passed and children have developed an age-appropriate understanding of death, you may notice more recognizable grief symptoms begin to show up. But if a child doesn’t appear sad right away, it doesn’t mean they aren’t grieving.

Difference 2: Grieving in Bits and Pieces

Children process their feelings differently than adults do when it comes to grief. A bereaved adult is likely to feel their grief intensely for weeks, months, or even years after a loss. They may have to work hard to give themselves breaks from grieving, so it doesn’t overwhelm them. Adult grief is ever-present, and the feelings tend to exist even when the griever is focusing on other tasks.

This isn’t how grief works for most children. Kids are much more able to jump in and out of grief. It’s normal for a child to cry and have intense feelings for a short period of time, before seemingly moving on to another activity, like playing with friends or watching a show.

This kind of back-and-forth would seem weird if an adult did it, but it’s perfectly normal for kids. Adults have a much bigger emotional capacity than kids do: they can tolerate a lot more before getting overwhelmed. If you imagine that an adult’s capacity for grief is like a big empty cup, a child’s might only be a tiny thimble. Once a child’s thimble is full, they need to step away from their grief process for a while, and return when they’re ready to handle some more.

Difference 3: Kids Feel Grief in Their Bodies

Studies have shown that kids are much more likely than adults to have physical pain and other body-based symptoms as part of their grief. This may be, in part, because it’s harder for kids to put their feelings into words. Instead, they hold on to all those feelings inside, and they show up in other ways.

It’s common for kids to complain of headaches and stomach aches as a result of the stress. They may also feel fatigued, dizzy, or have trouble focusing on things. Sleep and eating habits can change, too: bereaved children may have poor appetites or trouble falling asleep at night.

It’s always a good idea to talk to a doctor if your child isn’t feeling well. However, if your child’s symptoms don’t have a clear cause, they might be an outward sign of your child’s grief.

Different Signs of Grief in Preschoolers (3-5 Years)

Little children are in the earliest stage of understanding death. They’ve probably seen movies or cartoons in which characters die, and this might be their only basis for comparison. Children may assume death means that a person has gone away, fallen asleep, or otherwise left them in a way that is not permanent. They may also worry about whether or not their loved one is afraid or feeling pain.

Any stressful event can cause regressions for preschool-aged kids, and death is no different. You may notice your 3, 4, or 5-year old returning to earlier habits, like thumb-sucking or bedwetting. Your child may be extra clingy for a while, or have trouble sleeping alone when they were once independent.

You might also notice that themes or details from your loved one’s death show up in your child’s play. While it might be a surprise to see your child having a funeral for a Barbie doll, or re-enacting an accident with toy cars, this is usually a healthy sign. Children process feelings through play, so these types of activities help kids make sense of what has just happened in their world. If the play is prolonged, rigidly repetitive, or seems to make your child upset instead of relieved, it might be worth speaking to your child’s doctor or a children’s grief counselor.

What Grief Can Look Like for Big Kids (6-10 Years)

6, 7, 8, 9, and 10-year-olds have their own unique experiences during the grieving process, including magical thinking.

Older children have a more solid understanding of death, which is both good and bad news. On one hand, it’s easier to help kids in this age range understand what’s going on when a loved one dies. On the other, kids tend to develop their intellectual ability to understand death before they build the emotional skills they need handle the strong feelings of grief. As a result, elementary-aged kids may have the hardest time coping with loss.

Big kids may be wondering why their loved one died, and searching for explanations that make sense to them. Kids in the younger end of this age range often believe that their thoughts and feelings have a direct influence on the outside world. This can lead to children worry that something they said, did, or thought might have caused their loved one’s death. It’s important for children to have a clear explanation for their loved one’s cause of death that removes any possible blame for what happened.

Children may ask repeated “why” questions at this age. It’s likely, though, that your grade schooler will show you their feelings more than they tell them. Physical complaints are common among this age group, and so are problems with sleeping and difficulty concentrating at school. Keep an eye on how your big kid handles school and friends in general: some children may throw themselves into too many activities in an attempt to cope, while others may withdraw from friends and hobbies they once enjoyed.

How Do Tweens and Teens Grieve Differently?

Tweens and teens are able to think more abstractly, which means they’re able to grasp the concept of death in ways that younger kids can’t. They understand that death is permanent, and they may wonder about their own mortality or the afterlife when a loved one dies. Even though tweens and teens think about death in similar ways to adults, they still face their own unique emotional challenges.

As kids near the teen years, their friend group becomes increasingly central to their lives. This means tweens and teens may be more likely to turn to their friends for comfort when a loved one dies. If your child is part of a healthy, mature friend group, this can be a great source of support. However, it can be hard for peers who haven’t experienced their own loss to empathize in the way that grieving teens need.

Depending on your relationship with your tween or teen, you may notice that relying more on friends for support means you hear less about your child’s grief. Changes in grades, dropping out of school activities, and self-isolating can all be ways that older kids show they’re struggling with grief. It’s also common for kids in this age range to compare their situation to non-bereaved friends, so keep an eye out for unusual arguing or difficulties with peers. Death is unfair, and it’s easy to feel jealous or angry at a friend who complains about their family when you’ve just suffered a loss in yours.

Finally, tweens and teens are more likely than younger kids to find unhealthy or harmful ways to cope with grief. They may have access to drugs or alcohol, or may use self-harm as a way to deal with strong feelings. Any signs that a child may be considering self-harm or suicide should be taken very seriously, especially when a child is grieving.

Grief Timelines Look Different for Kids, Too

Grief can be a lifelong process, and this is especially true for children. Many kids start working through their grief before they fully understand the concept of death. This doesn’t make their grief any less valid or painful, but it does mean they’re likely to revisit their grief as they age. As children mature, they may understand their loss in new ways, and more fully grasp everything they will miss out on in the future with their loved one.

Milestones like special birthdays, graduations, and other coming of age traditions can rekindle grieving feelings for kids. These events, while happy, are also a reminder that someone is missing from the family. This is especially true for children who have lost a parent or caregiver. As kids become young adults, they may be increasingly aware of how their early loss will affect their weddings, the birth of their children, and other life milestones.

If you notice your child has a hard time around the holidays, or enters a period of intense grief when a milestone occurs, it’s okay. It doesn’t mean your child’s grief is getting worse or moving backwards. They’re just looking at their grief with a new perspective and working through it in a deeper way.

Grief Help Made Especially for Kids

I hope you reached this page either out of curiosity, or to prepare for the future, just in case. If that’s not true, and you’re here because your child is grieving, I have a resource to share with you.

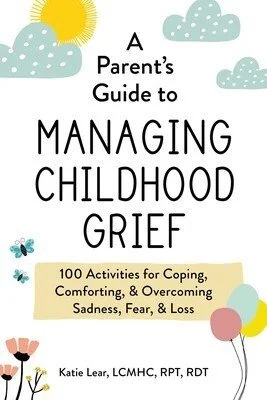

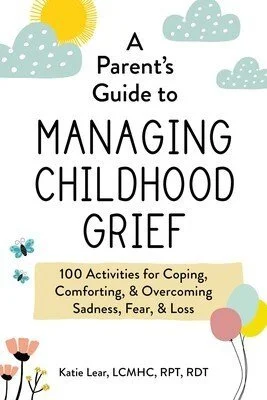

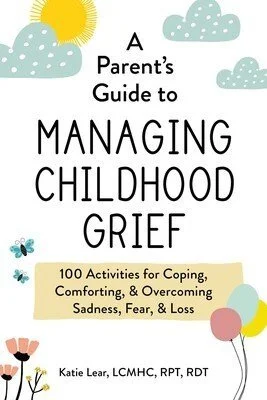

I wrote an activity book, A Parent’s Guide to Managing Childhood Grief, that was created to help parents understand and support the unique ways that children grieve. The book contains 100 playful and creative activities for kids ages 5-11, divided into categories to address some of the most common needs children and families face when a loved one dies.

If you’re wondering how to help your child understand what death means, or explain difficult details about a loved one’s passing, you’ll find scripts inside to help. There are also chapters devoted to safely expressing feelings like guilt, anger, fear, and sadness that tend to show up during a child’s grieving process. Finally, you’ll find activities you and your child can complete together to encourage a sense of safety, meaning, and hope after grief.

A Parent’s Guide to Managing Childhood Grief is available at all major bookstores, including Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and independent bookstores.